The use of any content on this blog to train AI is prohibited.

I happened to see the film Words of War while reading Michelle Johnston’s novel The Revisionists—an amazing coincidence, given both are about the North Caucasus area, a part of the world I (possibly like many in the West) know little about, and that The Revisionists is dedicated to Russian journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya, the subject of Words of War. I am grateful to both of these works for bringing these places so wonderfully alive in my imagination, and in the process filling in some yawning gaps in my knowledge.

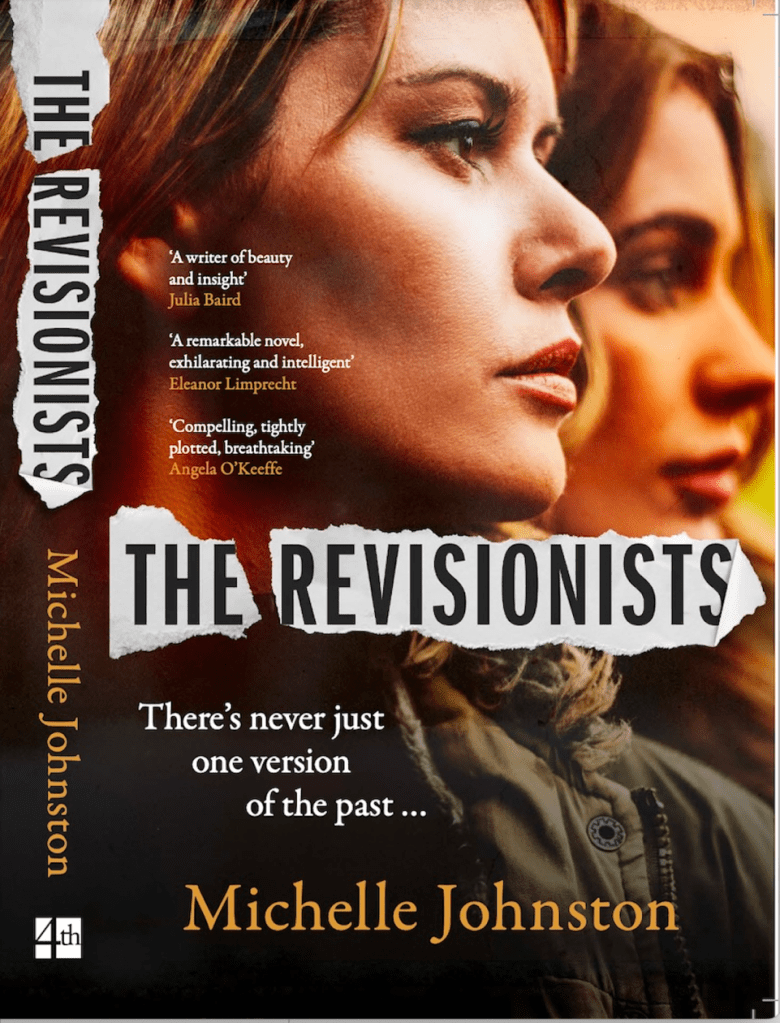

Michelle Johnston manages to excel in two demanding professions: author and emergency physician. If only she’d write a book about how; it would be a bestseller. She is a Staff Specialist at the Royal Perth Hospital Emergency Department, a busy inner-city trauma centre where she works as both clinician and teacher. The Revisionists is Michelle’s third novel, following Dustfall (2019, shortlisted for the MUD Literary Prize for a debut novel) and Tiny Uncertain Miracles (2022). Michelle says her days are mostly spent searching for the beauty and awe in a frequently brutal reality.

Here is the blurb for The Revisionists:

Upper East Side, Manhattan, 2023: Christine Campbell, former journalist, turns on the television to watch a documentary paying homage to her Pulitzer Prize-shortlisted coverage of the unrest in 1999 in the North Caucasus. She is newly widowed, wealthy and attempting to write a memoir celebrating her bold life and significant achievements in writing about the silencing of women during conflict.

But truth has a way of resurfacing, even when buried deep beneath money, memory and reinvention. When Dr Frankie Pearson, Christine’s oldest—and estranged—friend, knocks on her door, the pair must reconcile their memories and come to terms with the far-reaching and disastrous decisions they both made over twenty years ago. What really happened in that small mountain village in Dagestan in the dying days of the millennium, while Christine was hellbent on getting the scoop of a lifetime?

Over to Michelle…

2 things that inspired the book

The might and courage of female conflict correspondents. The Revisionists is dedicated to Anna Politkovskaya and Marie Colvin, both heroic foreign correspondents who were assassinated in the course of reporting on war. The concept of truth in journalism was a powerful driver for me when writing this book: who owns the truth (reflected in our current Kafkaesque nightmare of a media landscape controlled by billionaires and tyrants buying a version of the world they spray out for their own benefit), how our memories distort our own personal versions of truth, and how language is used and misused for propaganda and political purpose.

Human flaws and folly. I had in my mind a character, a woman, with warring personality traits—great principle, but also the desire for validation and acclaim. Essentially, I let those two characteristics go into battle inside my poor protagonist, Christine Campbell (‘conflict correspondent with a feminist bent’), launching her into a tinderbox of a setting (a war-torn republic in the North Caucasus on the precipice of further descent into conflict and invasion), and seeing how those variables would play out. How much would she sacrifice to make a name for herself? How would she honour the women whose voices she was hoping to showcase?

2 places connected with the book

Dagestan. One of seven Russian republics making up the North Caucasus, Dagestan is a place of immense contradictions: towering, mountainous beauty and desperate poverty; bounteous generosity and hospitality and a republic known for its fighters. It is deeply Islamic and is the nidus of a volatile, far-reaching history, a place subject to constant invasion, reinvasion and reinvention. Few westerners have heard of this incredible republic nestled on the Caspian Sea, and the moment I did, I became obsessed with knowing more. A tiny slice of time got its hooks into me—the invasion of Dagestan in 1999, during which Chechen warlords made a bid for a united Islamic State but instead found themselves facing the fury of a then unknown and newly appointed prime minister, Vladimir Putin, who put into motion the horrific slaughter and devastation of the second Chechen War. This laid the ground for Christine Campbell to search for her story and, by default, herself.

New York. Having spent a good deal of time as a wanderer in that human storm of a city, a flâneur, a small-town girl in the epicentre of man-made energy, I sent Christine there to live out her days of false memory and justification and misery despite her money. I had been influenced by all the places that make an appearance in the book. A graffiti strewn apartment on Orchard Street, the white quiet of Poets House, dinners at Gramercy Tavern, the subway, the Strand bookstore, the cafes. And there, in Manhattan, Christine would have grown old, taking her retrospective falsification and excuses to her grave, had it not been for her childhood friend Frankie, with whom she spent time in Dagestan, turning up on her doorstep to challenge her on those explosive events of time past.

2 things that confuse readers

Angela Hollis’s poetry. For reasons that become quite clear by the end of The Revisionists, Angela, the extraordinary and highly regarded conflict correspondent who takes Christine under her wing, has a number of poems scattered throughout the book. In fact, one of her pieces opens the book: Time rumbles. It’s a low growl between the shoulder blades, in the bones, deep in the chest. Time rumbles like ocean currents, like drowning stars. It’s the sound of a rough wind at dawn, of the trudge of the displaced through the dark. People commonly tell me that they googled ‘Angela Hollis. Poetry’ and are perturbed when they find no results. ‘Where did the poetry come from?’ they ask. ‘I wrote it,’ I reply, which doesn’t seem to satisfy them but makes me oddly happy.

Is Khumsutl a real place? Because I (author as god) was going to do terrible things to the town where Christine and Frankie worked, alongside the beloved siblings Patimat and Murtuz, I needed to make up a place that would not complain if I let loose a bomb or two on it. Strangely, I had written several drafts of The Revisionists by the time it became clear that I had to travel there. I would never have been able to stand up and look readers in the eye (metaphorically or literally), I would have had no authenticity or authority to write the book if I hadn’t travelled there. (Reader, this is not recommended: the North Caucasus is on the DFAT ‘do not travel under any circumstances’ advice.) However, go I had to. And it was magnificent. The strange part is that I had made up a village based on my research which provided the setting in the drafts I’d written prior to travelling there, and on one cold night in the mountains we found ourselves in an utterly uncanny likeness of Khumsutl, with a small abandoned medical clinic, a schoolhouse, a jumble of architecture, a hundred-year-old widow at the top of a tower. It was one of those exquisite moments where the universe says to you: yes, this is the book you must write, I give you this magic.

The Revisionists is in bookshops and available in online stores now

Find out more at HarperCollins

Follow Michelle via her website

Read a review: ANZ LitLovers; ArtsHub

Photo credits: Photos of Dagestan by the author—women of the village of Shitli; the ghost village of Gamsutl; the silversmithing village of Kubachi

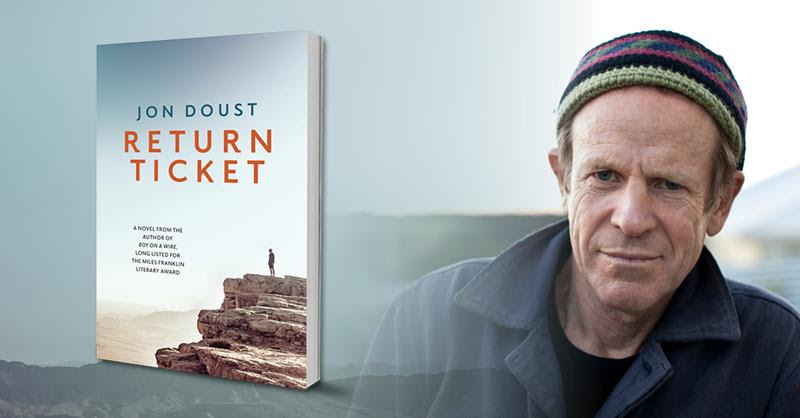

It’s impossible to be in a room with Jon Doust and not end up laughing at something—often yourself! I also credit him with teaching me a few things about the proper way to breathe while speaking to an audience, after he noticed that I wasn’t really breathing at all! Which is a roundabout way of saying he’s a generous man as well as a funny one.

It’s impossible to be in a room with Jon Doust and not end up laughing at something—often yourself! I also credit him with teaching me a few things about the proper way to breathe while speaking to an audience, after he noticed that I wasn’t really breathing at all! Which is a roundabout way of saying he’s a generous man as well as a funny one.

![Narrawong State Forest[2]](https://amandacurtin.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/narrawong-state-forest2.jpg)