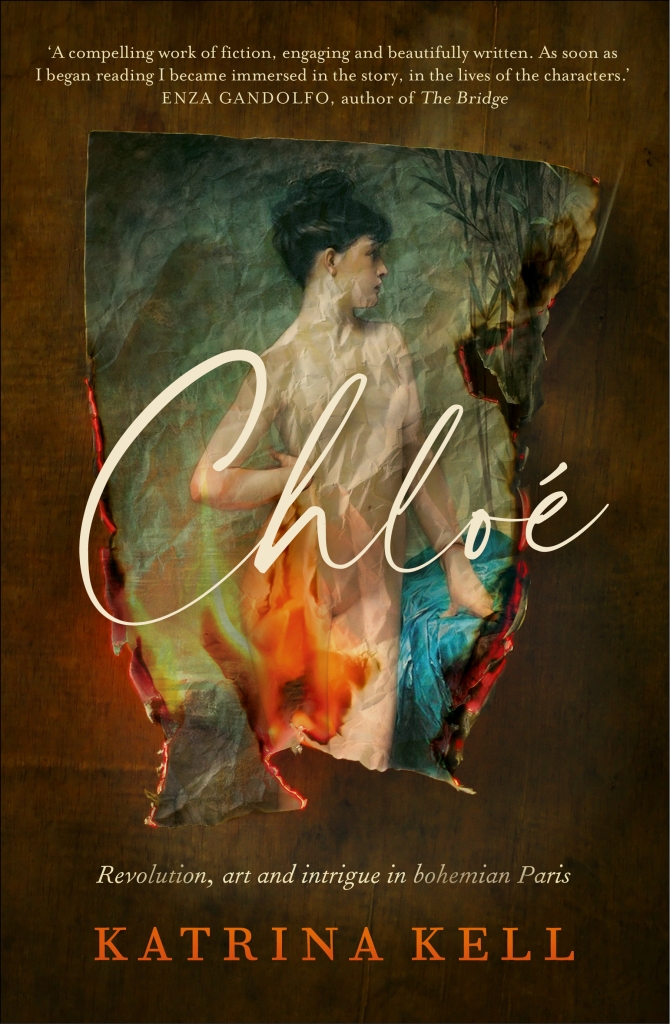

I love creative projects that cross artforms in some way. My own writing has drawn on sculpture, art and dance, and I have been privileged and truly thrilled to have some of my works inspire paintings, a visual arts installation and, most recently, a concert by a symphony orchestra. So I was immediately drawn to Chloé, a newly released novel by Western Australian author Katrina Kell.

Chloé was inspired by the famous painting of the same name that hangs in the main bar of the Melbourne hotel Young and Jackson. It is a once-seen-never-forgotten work by French artist Jules Lefebvre—a large, lush nude that speaks of another time, a distant world. Given the iconic place it has come to have in Melbourne’s history (I’ll let Katrina tell you about that), my only surprise is that it’s taken so long for a writer to take it on.

I think Katrina has done Chloé proud.

Katrina is also the author of two YA novels, as well as short fiction, poetry and essays, and the unpublished manuscript of Chloé won an Australian Society of Authors Award Mentorship. She lives and works in Boorloo (Perth) and is an Honorary Research Associate at Murdoch University.

Look at this gorgeous cover!

A riveting novel based on the true story of the brave, enigmatic young woman who modelled for one of Australia’s most famous paintings.

Taking the reader from Victoria’s wild shipwreck coast to the artists’ studios of revolutionary Paris and the bloody battlefields of Flanders, this sweeping novel reimagines the volatile history of the beautiful and enigmatic young woman immortalised in one of Australia’s most iconic paintings. Created in Paris in 1875, Chloé, Jules Lefebvre’s depiction of a naked water nymph, was brought to Melbourne’s Young & Jackson Hotel in 1909, where it has hung ever since.

In this passionate, luminous retelling, Katrina Kell seeks to unlock the riddle behind the girl on the canvas, known to history only as Marie. In doing so, she weaves the compelling story of an incandescent spirit—a woman with the strength to defy the boundaries of class and convention in order to survive, and an enduring power to influence the lives of others across time and distance.

France in an Aussie pub

AC: Katrina, in order to imagine the creation of a painting and the lives of its artist and model, it’s necessary to spend a long time minutely studying its composition, its brushstrokes, its light and shadow, the background, the tone of the model’s skin, the lift of her shoulder, the expression on her half-turned face. Did you have the opportunity to do that in person at the outset of your project, or sometime after you’d been researching the painting, and the story, at a distance? I’m wondering what it felt like for you, seeing the painting for the first time.

KK: I saw Chloé at Young and Jackson Hotel in Melbourne early in my research journey. The nude figure depicted in the artwork appears almost life-size. Her gilt-framed image dominates, some might say rules, the public bar she is displayed in. I was immediately struck by the intensity of the Parisian model’s expression. Her glowing corporeality was palpable, but it was her face, her sombre countenance, that drew me into the picture. There was such sadness in her gaze, overlain by an edge of defiance. She was far more complex and intense than the titular naiad Lefebvre claims he painted.

Separating fact from fiction

AC: I imagine your first imperative as a researcher was to explore the lives of the model Marie Peregrine and the artist Jules Lefebvre. I’m sure the latter was easier than the former! Was there anything at all to find concerning Marie? Were there clues, other than those to be found in the very significant visual image in Chloé, that gave you a way into her character?

KK: Researching Lefebvre’s artistic career was certainly easier, but learning about his character proved much more challenging. Reliable material was only available in French. Initially, I was helped by a friend, a professional translator, until I grew confident in my translations. In Paris, I researched in several French institutions and gained access to the space where Lefebvre painted Chloé. It was a poignant experience, climbing the marble spiral staircase to his former atelier, and feeling the ambiance in the chamber where Marie had once posed for the artist.

There were a few sketchy clues about Marie, and the challenge was to separate fact from fiction. Chloé has been a beloved cultural icon for over a century. Myths about Marie and Jules Lefebvre are deeply entrenched and often reductive, so I needed to mine the few nuggets of truth to get to the heart of Marie’s story.

The Anglo-Irish writer George Moore (1852–1933) wrote about a girl named Marie in his memoir Confessions of a Young Man (1888). Moore claimed she was the model for ‘Lefebvre’s Chloé’. In his auto-fictional short story ‘The End of Marie Pellegrin’, he wrote again of the Parisian girl I suspect was Chloé’s model. Moore’s accounts of Marie’s turbulent life closely mirror details shared by Lefebvre during a conversation he had with the American journalist Lucy Hamilton Hooper (1835–1893). It was a spine-tingling moment when I read Hooper’s interview in her ‘Paris Letters’ column in the Appletons’ Journal. I was aware of the oppression and threats to proletarian women following the violent crushing of the revolutionary Paris Commune, and it was becoming clear that Marie’s lived experience would have been fraught with trauma and danger.

‘Having a drink with Chloé’

AC: A second story is woven through the novel—set in Australia, during the First World War. First, could you tell us about the significance of the painting Chloé to Australian soldiers at that time?

KK: ‘Having a drink with Chloé’ has been a ‘good luck’ ritual for Australian soldiers since the First World War. When Chloé was hung in Young and Jackson’s in 1909, the pub, opposite Flinders Street Railway Station, quickly became a drawcard. During this era, many young men would rarely have seen an unclothed woman. Chloé may have been their first and only chance of viewing a naked female body. Some even wrote love letters to the famous painting, and Chloé’s ‘good luck’ symbolism continued over many decades and military conflicts. As West Australian traveller Peter Graeme wrote, of a soldier he saw downing beers in front of the painting in honour of his fallen mates, Chloé may have been ‘the symbol of the feminine side of his life. That part which he puts away from him, except in his inarticulate dreams’ (see my article in The Conversation).

Ancestral links

AC: And the twin brothers, Rory and Paddy, who enlist in the war: how did their story evolve?

KK: My family heritage is from south-western Victoria, so setting this story thread there felt intuitive. My great-great-great-grandfather was captain of the Thistle, the shipwrecked schooner that lies offshore at Port Fairy beach in Eastern Maar Country. The character Abby, Rory and Paddy’s mother, pays homage to my Irish convict ancestor, Abby Desmond, a young woman who arrived in chains but managed to prevail and raise a family here. It was a joy to spend time researching and establishing settings in and around Port Fairy, and the boys’ story evolved quite naturally. It was also easy to imagine how challenging life would have been for a woman like Abby in this beautiful, rugged region.

Castor and Pollux

AC: There are several links—some surprising—between the French and Australian stories. I especially liked the use of the mythological figures Castor and Pollux, and I’m wondering whether the Paris zoo elephants named after those figures might have inspired that link.

KK: My mother, Zant, is an identical twin, and her star sign is Gemini. Her Irish father, who loved astronomy, shared the story of Castor and Pollux with his twin daughters. Mum shared her father’s stories with us. She loved to point to Orion’s Belt in the night sky and show us the twin stars that meant so much to her. So it felt natural that Rory and Paddy’s father, an ocean fisherman, would share the story of Castor and Pollux, the twin gods who rescued shipwrecked sailors. When I learned of the tragic fate of the Paris Zoo elephants, I was moved by how their story seemed to resonate with the wartime experiences of Rory and Paddy. It was a link between France and Australia that emerged serendipitously.

Researching a paradoxical world

AC: I was distraught on reading the fate of the elephants—so emblematic of Paris’s inequities: obscene excess at a time of desperate hunger. Which is a roundabout way of leading in to a question about the turbulent, paradoxical world Marie and her mother Noemi lived in: on the one hand, war, revolution, starvation, persecution; on the other, the flourishing of French culture. It’s a daunting historical canvas. How did you go about your research?

KK: It certainly was a paradoxical world and quite the minefield to research. I read numerous accounts of the Franco-Prussian War and the oppression of the Paris Commune and how the rise of Impressionist art cast a veil of light and colour over a chapter of violence and darkness. Louise Michell, the revolutionary leader, was a rich source of inspiration. Her first-hand accounts of the Siege of Paris and the crushing of the Commune richly informed the novel. I discovered other first-hand accounts written by Parisians at the time and a collection of illuminating letters between Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin (George Sand) and Gustave Flaubert during the final days of the Commune. Lucy Hooper, an American journalist based in Paris, wrote regular columns on art, culture, and the day-to-day life of Paris in the 1870s. I also read the work of art historians Hollis Clayson, Gabriel P. Weisberg and Jane R. Becker, as well as George Moore’s memoirs of his life as a young art student at the Académie Julian in Paris.

Being there

AC: I know you had the opportunity, during your extensive research, to visit Paris and other places inhabited by your characters. Can you tell us about the experience of ‘being there’ and whether it had an effect on the development of the novel?

KK: Yes, the experience of ‘being there’ was such a privilege. Walking on the same cobbled streets Marie would have walked on during her lifetime and standing in the space where Chloe was painted. Soaking up the vibrant atmosphere of the Passage de Panoramas, the glorious glass-roofed arcade where the Académie Julian was located. One of the most pivotal and inspiring moments was exploring the paths and sepulchres at Montmartre cemetery. The black charring on tombstones evoked the fighting that once took place there, and I was awestruck by the voluminous mausoleums, the realisation that a fugitive could easily have made a home in one. Visiting the Somme region was equally important, especially experiencing, albeit vicariously, the terrible claustrophobia and the sounds and sights of First World War trench warfare at the Musée Somme 1916 in Albert. And, of course, seeing Chloé in all her glory at Young and Jackson’s was an extraordinary moment.

Recuperating the past

AC: Katrina, this is your first novel for adult readers, and your first foray into historical fiction. Do you see yourself continuing to pursue stories of the past?

KK: Yes, I do, absolutely. I am passionate about recuperating women’s stories, especially stories of creative women who have been ignored in the annals of history. It’s exciting to be researching and laying down the bones of my next novel. This story will explore another fascinating and surprising link between Australian and French art history.

Chloé is published by Echo Publishing

Follow Katrina on Facebook or visit her website

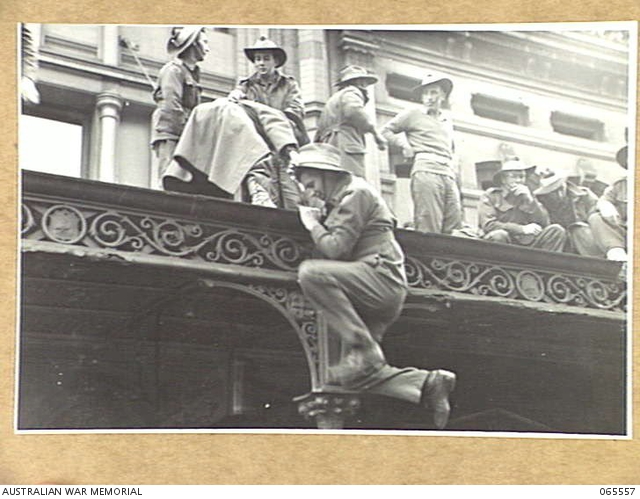

Photo credits: author photo J.J. Gately Photography; Katrina and Chloé photo Dave Kell; Jules Joseph Lefebvre photo public domain; Jules Lefebvre in his studio (1882) photo by Émile Bénard, public domain; Barricade de la place Blanche, défendue par des femmes pendant la semaine sanglante (Barricade at place Blanche, defended by women during the bloody week), lithographie, Musée Carnavalet, public domain; soldiers climbing onto the roof of Young and Jackson Hotel, World War 2, photo Robert Bruce Irving, Australian War Memorial Collection AWM065557, public domain; Arrest of Louise Michel in May 1871, Musée d’Art et Histoire du Saint-Denis, public domain; Montmartre Cemetery sepulchre photo by author