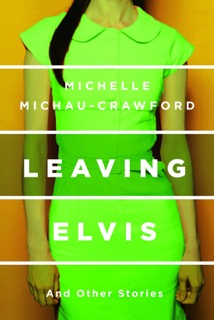

I’m delighted that the first post for 2016 in my 2, 2 and 2 series, which highlights writers with new books, is Michelle Michau-Crawford and her debut short story collection Leaving Elvis and Other Stories (UWA Publishing). Michelle was one of the ‘next wave’ women writers featured on the blog in 2014, and I also had the great pleasure of editing this remarkable collection.

I’m delighted that the first post for 2016 in my 2, 2 and 2 series, which highlights writers with new books, is Michelle Michau-Crawford and her debut short story collection Leaving Elvis and Other Stories (UWA Publishing). Michelle was one of the ‘next wave’ women writers featured on the blog in 2014, and I also had the great pleasure of editing this remarkable collection.

If the name of the author or the title story sounds familiar, you might be recalling that Michelle won the prestigious ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize in 2013 for the story ‘Leaving Elvis’, which was subsequently published in ABR.

Michelle has worked as a university lecturer, speechwriter, researcher and public relations officer, and lives in Perth with her menagerie in a house surrounded by vegetable gardens and fruit trees.

Here is the blurb for Leaving Elvis:

We’re travelling light, without excess, into our future. Gran had been rough as she uncurled my hands from their position, gripped around the open car doorframe, and shoved me into the passenger seat.

A man returns from World War II and struggles to come to terms with what has happened in his absence. Almost seventy years later, his middle-aged granddaughter packs up her late grandmother’s home and discovers more than she had bargained for. These two stories book-end thirteen closely linked stories of one family and the rippling of consequences across three generations, played out against the backdrop of a changing Australia.

A debut collection—as powerful as it is tender—from the winner of the 2013 ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize.

And now over to Michelle…

2 things that inspired my book

1 This collection started as a sort of side-project to take me away from the novel I thought I should be finishing. In a roundabout way, a gentle rejection was the inspiration for finally letting go of something that had ceased to bring me any real satisfaction in order to focus on something that was bringing me satisfaction. By the time I’d completed one story and some first drafts of several more short stories, I had grown to resent sitting down to work on the novel. I had basically killed that work by overwriting and overthinking it. But somewhere along the way I had convinced myself that without seeing it through to publication, I was a phoney, and that once it was done I could put it aside and ‘write more short stories’. One day I braved up enough to share the manuscript with a publisher for feedback, and when we met to discuss it she identified what I already knew. We suggested putting the manuscript aside for a while. I was so relieved that I may have jumped up from my chair and given her a hug and said something along the lines of ‘Thank goodness, now I can go to work on what I really want to be doing.’ I seem to recall that I then proceeded to babble on about the closely linked stories I was working on.

That publisher was Terri-ann White from UWA Publishing, so the rejection story had a very happy ending for me!

2 For as long as I can remember I have had a fascination with abandoned and lost children. I was born just six months before the Beaumont children disappeared in January 1966, and from early childhood always knew that children could simply cease to exist in the blink of an eye. In 2005 I began what would amount to eight years’ work (not full-time, I might add) on what eventually became the short story ‘Leaving Elvis’. I was researching for an Honours project at the time, looking at memory and trauma in Australian literature. My particular interest at that point was in intergenerational trauma and patterns of behaviour, and abandonment, in all its various forms, of children by adults. I came across Peter Pierce’s The Country of Lost Children: An Australian Anxiety (1999). In his book Pierce describes the way that the theme of abandonment has flowed through non-Indigenous Australian literature since white settlement, and contemplates the contemporary ‘lost child’ as a victim of white society itself. Where early writings centred on fears about a hostile and unforgiving land, writing changed direction around the 1950s, a period generally recognised as a time when there was a loss of innocence in white Australian culture. Without intending to, and certainly without realising it until well into the writing of the collection, I appear to have continued this pattern and written a book that explores, in part, the lost child as victim of society itself, along with intergenerational patterns of behaviour in a period commencing around the 1950s.

2 places connected with my book

1 The small ‘home’ town that features in a number of stories appears to be somewhere in or near the Western Australian wheat belt. However, I have intentionally left the location unspecific so that by changing a few minor details it could be just about any small town or outer suburb in Australia where people have somehow found themselves living. It is the sort of place where, with no real aspirations or ambition to spend a whole life there, several generations of one family now reside, doing the best they can. Some of the people in these stories are prone to plotting or dreaming about escaping to that mythical ‘somewhere else’ where they can leave their past behind and live a more fulfilling life. Ultimately, when it comes down to it, wherever they may find themselves living, this is the only place they have to come back to in order to feel some sense of connection and belonging to a physical environment.

2 The sky is a place that is significant in Louise’s adult life. In her years in Europe, it is the thought of the specific colours and expansiveness of the Australian sky that increases both her longing for home and her sense of isolation. At one point, she has a fling with an English artist who’d tried to paint the Australian sky just so she’d have an opportunity to be able to talk about home and the sky with him. Many years later, in another story, she realises that she has to return to Australia, to her home town, while looking up at the sky of the northern hemisphere with it’s ‘skew-whiff shades’ that will never be right.

2 favourite moments in the book

1 In the story The Light, there is a moment where Natalie, having reached rock-bottom, and with every reason not to feel good about anything at that particular time in her life, sits in an isolated place in nature and feels a few fleeting moments of calm. ‘She’s never had religion, but there’s something soothing and spiritual-like about being here, and she feels close to relaxed, sitting there with the sun disappearing while the immense orange sky turns purple and grey.’ Often the people in these stories struggle to feel they belong and maintain connections, Natalie perhaps more so than others. But that passing moment of recognition that there is something bigger than her and her problems is enough.

2 I’m interested in those vulnerable moments in childhood and adolescence where there is an understanding in the young that there is something going on within their bodies and minds, but still an inability to fully understand or articulate those changes. There is a moment in the story ‘Rendezvous’ where this occurs. Louise reflects on being about eleven years old when she’d stood in front of her friend Leslie Mulligan: ‘pulling petals off a daisy one at a time, she’d stared him in the face, he loves me, he loves me not.’ Watching her friend grow pink and embarrassed, she’d run off laughing, knowing that she had ‘some sort of mysterious power over him, but not yet knowing how or when to use it.’ Confused by both his and her reaction to the experience, she hides until Leslie finally gives up searching for her and goes home.

Leaving Elvis and Other Stories will be available in bookshops in February 2016

Find out more at UWA Publishing

Visit Michelle’s website or connect via her Facebook page

Michelle will be a guest of the Perth Writers Festival 2016