I’m delighted to be featuring in this post one of my favourite Western Australian authors and another new book that celebrates Western Australian history. Julia Lawrinson’s Trapped!, a verse novel for middle readers, draws on an episode from the rich history of the Eastern Goldfields and is, I’m sure, destined to become a favourite with schools, libraries and young readers.

Julia is one of the most accomplished—and prolific—writers I know, and a truly impressive speaker. Her author biography only scratches the surface of her career, but here it is: She has published more than fifteen books for children and young people, from a picture book to books for older teenagers, and in 2024 published a memoir called How to Avoid a Happy Life [highly recommended]. Her books have been recognised in the Children’s Book Council Awards, the WA Premier’s Book Awards and the Queensland Literary Awards, and she has presented to schools across Australia, in Singapore and in Bali. She is an enthusiastic adult learner of Indonesian, yoga and the cello. Her favourite place on earth is the dog park.

The Julia Lawrinson section of my bookcase is huge!

In 1907, the mining town of Bonnie Vale experiences a sudden deluge of rain that floods a gold mine while miners are still at work down the shaft.

Joe’s dad is one of them. And it soon becomes clear that he’s the only one who hasn’t made it back out yet. Where is he? Why didn’t he escape with the others? And more importantly, how will they rescue him?

Inspired by the true story of the trapped miner of Bonnie Vale and told in verse, Julia Lawrinson weaves a tale that will beckon readers down into the gold mine with Joe’s dad to find out how the rescue unfolded.

Panel by panel

AC: Julia, we’ve both wandered through the rooms at the wonderful Exhibition Museum at Coolgardie. Was it there that you first heard about the incredible rescue that is at the heart of this new novel? I seem to remember that the museum has one room dedicated to the story.

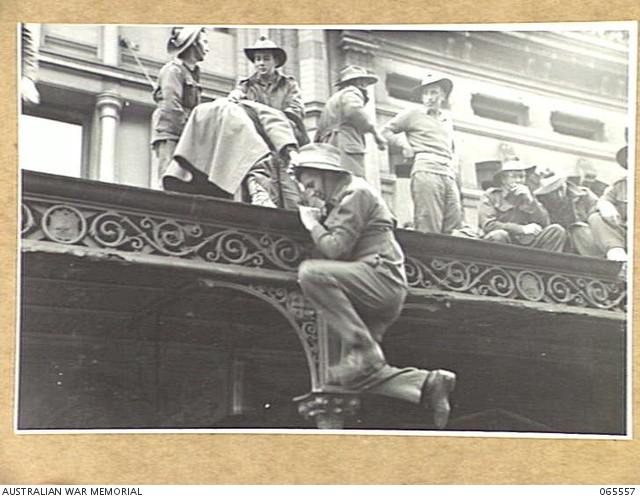

JL: Yes, it was—I had absolutely no idea of it, and once I’d gone through the story, panel by panel, I couldn’t believe that it wasn’t better known outside the goldfields. At the end of the story, you turn on a light, and there is a life-size reconstruction of the rise, complete with Varischetti in it, which was completely arresting.

From thriving town…

AC: Bonnie Vale, where the novel is set, was a mining town about 15 kilometres north of Coolgardie. I say was because it appears on the map today as just the name of a mine site. What was the town like in 1907, when your novel is set?

JL: In the goldfields of 1907, the gold rush was on the wane but was still attracting prospectors from all over the world. Bonnie Vale was gazetted in 1897, and had twelve streets and about as many mining operations, of which the Westralia mine was the biggest. It had about 1,000 official inhabitants, but hundreds more—like Modesto ‘Charlie’ Varischetti—lived in tents, shanties made of flat tin cans and brush shelters. There was a state school with either one or two teachers, a hotel built of iron, a post office, and all the trades you could want in 1907: blacksmiths, carpenters, butchers, a baker, a tinsmith and a plumber. There was Australian Rules football, foot racing and weekend cricket, including a women’s team, and an 11 kilometre cycling track. A Catholic priest visited from Coolgardie once a month.

…to ghost town

AC: As someone fascinated by the ghost towns of the Eastern Goldfields, I’m wondering whether you were able to visit the site during your research and, if so, whether there is any remaining physical evidence of the township that once existed there?

JL: I really wanted to go. I applied for two grants but didn’t get them, so had to rely on photographs and descriptions. I had been to Kalgoorlie and Boulder many times, and Coolgardie twice, so I tried to extrapolate a bit. Apparently there is nothing there now, but I would have liked to have stood on the ground and felt it.

A young person’s voice

AC: Trapped! is told through the eyes of Joe, the eldest son of the trapped miner, Modesto Varischetti. Was there a real Joe?

JL: There was a Joe (Giovanni, not Guiseppe), but he was Modesto’s brother, not his son. Varischetti did have a twelve-year-old at the time he was trapped, but she was a girl, and in Italy with her four younger siblings. The story needed the point of view of a young person involved and invested in the rescue, and so Joe was created.

Changing approach

AC: I’m interested in your decision to write the story in the form of a verse novel, which is, I think, a first for you. Could you talk, please, about why you chose this form and the technical challenges and opportunities it presented?

JL: Initially I wrote the novel alternating between Joe’s point of view and third person. I ended up getting bogged in detail and research—about everything from the mine to the living conditions to the school routine and children’s games. In despair over this unwieldy manuscript, I decided to try and cut it down to the absolute nuts and bolts of the story. Before I knew it, I had a few experimental pages of verse. I sent it to Cate Sutherland at Fremantle Press, and she loved it, so I kept going. I was focusing on what it sounded like, reading it.

The appeal of verse

AC: The novel’s intended readership is middle readers, defined as age eight and over (although I think it could be read and enjoyed by anyone). Does the verse novel genre have specific appeal for this age group?

JL: I hope so! Kids can sometimes be overwhelmed by blocks of text, especially in this digital age, and I think poetry as a format is much friendlier.

Divisions

AC: Apart from being a thrilling narrative of a near-impossible rescue, Trapped! is also a very skilfully told story about social divisions: the Italians and the ‘Britishers’, the working men and the bosses. Some people might be surprised to learn that Italian immigration to Western Australia began this early. What were the circumstances that led to the migration of Italians to the other side of the world in these early years of the twentieth century, and what attitudes did they find here?

JL: The agricultural poverty of northern Italy led many Italians to move from working in lead or zinc mining in that area in the late 1800s to the goldfields for work, mostly with the aim of sending money home to their families. But the attitude they found from the labouring ‘Britishers’, or Australians of British descent, was often harsh. One woman who grew up in Bonnie Vale from 1899 and lived there until 1911 said the mines chose to employ the Italians as ‘cheap labour’. She remembered some Italians walking seven miles from the train line to the Westralia mine, but were chased off: her mother, who ran the hotel, hid them wherever she could, in the pantry and under the bed, and told the men chasing them to take it up with the mine managers, not the poor Italians.*

There were Royal Commissions in 1902 and 1904 into foreign contract workers, focusing mostly on Italians. Even though the commissions concluded there was no undercutting of wages, the tension remained. In 1934 there was a riot in Kalgoorlie, aimed at ‘Dingbat Flat’, which housed Italians, Slavs and other southern Europeans.

My step-Nonna came to Western Australia as a child in the 1930s, and for all her days she remembered the terrible treatment she got from the other children, who made fun of her accent and the food she ate. Her stories were the basis of Joe’s treatment in the novel.

I think readers now will be surprised at how acrimonious the relationship was between Italians and Anglo Australians. To me it shows that divisions—even ones that appear stubborn and intractable—can eventually be overcome in the right circumstances.

A story revivified

AC: Given the dramatic nature of the Bonnie Vale mine collapse and the rescue of Varischetti, one might imagine it would be a story known to most Western Australians. It certainly held the attention of the state, the country and even the world while it was happening. But are you finding this is the case?

JL: No, the story is remarkably unknown—hence this book! There is a quote from The West Australian from 29 March 1907 which says: ‘Our educational authorities would do well to find a place in the school reading books for so inspiring a story from real life.’ It’s taken more than a century, but I hope Trapped! is it!

*The woman was interviewed by Tom Austen for his book The Entombed Miner (St George Books, 1986).

Trapped! is published by Fremantle Press

Follow Julia on Substack; contact her via her website or Fremantle Press